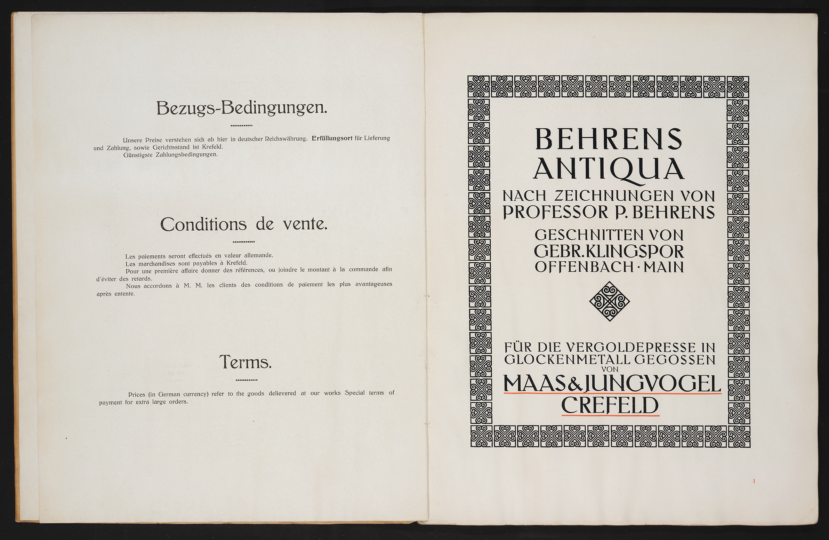

The image above shows the title page from Maas & Jungvogel’s brass-type specimen for the Behrens-Antiqua typeface (Allard Pierson, University of Amsterdam, call number KVB LPF 215). I’m beginning a new research project on the history of Germany’s brass-type foundries, particularly the companies like Maas & Jungvogel that were based in Krefeld. My project started with a small zine that I produced with students at the Hochschule Niederrhein during the 2021–22 winter semester about the Otto Kaestner GmbH, another Krefeld-based engraving firm manufacturing brass types. In the fall, I hope to continue my brass-types project: Krefeld celebrates its 650th birthday in 2023, and brass-type manufacture seems to me to have been the city’s greatest contribution to the history of typography.

Brass letters

In various ways, book-making and printing tradespersons have been using brass tools for as long as each craft has existed. In this project, I’m looking at two specific uses: Brass types for poster printing and brass types for bookbinders. Traditionally, bookbinders have used brass tools for their lettering longer than poster printers have used brass elements. Bookbinders have used brass stamps and other tools for centuries, and fonts of brass types for bookbinding must have been engraved or even cast for quite a long time. Those “pre-industrial” brass bookbinding tools would have been cut by hand.

The oldest specimen of brass types at the St Bride Library dates back to 1850. It shows “improved brass type” from William Day. Yet, type specimens aimed at bookbinders are at least a little older. The typefoundry at the Andreäische Buchhandlung in Frankfurt am Main published a specimen of bookbinder’s types in 1830. I had the German National Library digitize its copy, and you can view it here. Newspaper reports indicate that the same foundry – after the owner Benjamin Krebs renamed it after himself – published another specimen for bookbinders in 1851. Based on the 1830 specimen, I suspect that Krebs’ foundry was selling bookbinders fonts of type cast from normal type metal, just with a smaller number of total sorts than were sold to printers. Bookbinders don’t set as much text as printers did.

Albert Falckenberg & Comp.’s printing house in Magdeburg also operated a typefoundry. By the late 1860s, it was producing brass types. The company exhibited some at the 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna. I suspect it was the first German firm to manufacture sand-cast brass typefaces for bookbinders. At least in the late 1860s, it cast its brass types for bookbinders on type-heigh bodies. By the 20th century, however, most brass fonts for bookbinders were not type-high but on much shorter bodies instead.

Brass “poster types” were intended for printing on more surfaces than just paper. These letters were always type-high. That allowed printers to use them together with foundry types and wood-type fonts. The earliest German design patent given for brass poster types I’ve found so far was issued to F. A. Rost in Offenbach am Main on 29. April 1881. However, poster-type makers like Rost probably used brass in what Pierre Pané-Farré describes as “non-industrial” methods.

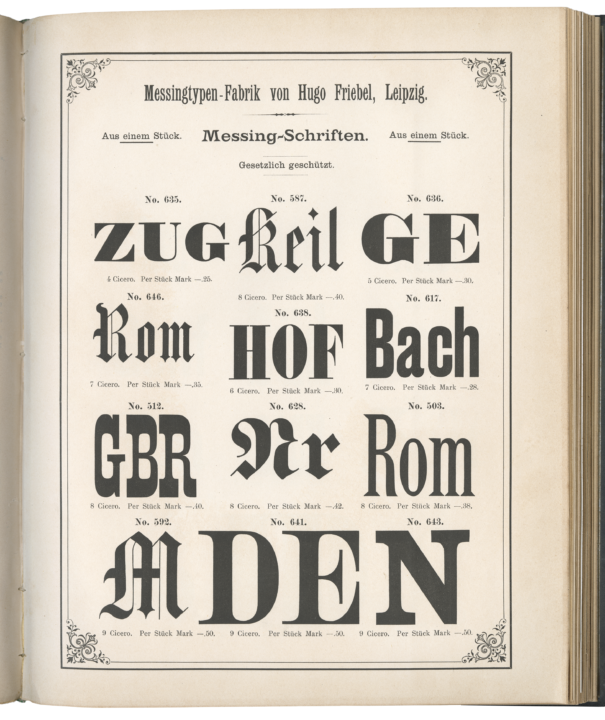

Specimen sheet from Hugo Friebel’s brass-type factory in Leipzig, delivered as a supplement to the January 1887 issue of Archiv für Buchdruckerkunst und verwandte Geschäftszweige. Friebel’s factory registered itself as “Hugo Friebel & Co.” in May 1887. The company’s owners were the punchcutter Franz Hugo Friebel, the technician Julius Justus Philipp Peter, and the salesman Wilhelm Eugen Theodor Mendheim [source].

A new method of the industrial manufacturing for brass types for poster printing was patented in the 1880s. As Wilhelm Jacob mentioned in a 1905 Klimsch’s Jahrbuch article, [“industrial”] brass types were invented in the latter half of the 19th century by a punchcutter named Friebel. I suspect that Jacob meant Franz Hugo Friebel, who was selling brass types in Leipzig by 1886, if not a few years before. According to his advertising, Hugo Friebel had patented a kind of brass type that was cast in one piece, the inside of which was hollow. Friebel’s products were aimed at the poster-printing market. His company argued their brass alloy was more durable than wood type. I do not know if Hugo Friebel was related to Theodor Friebel, an independent punchcutter also based in Leipzig. Theodor Friebel, who had a somewhat indirect connection to the Akzidenz-Grotesk typeface family, registered product patents of his own, including at least one matrix-making invention in 1882. As a punchcutter and type designer, Theodor Friebel carried out commissions for several foundries, including Bauer & Co., Julius Klinkhardt, and J. H. Rust & Co.

Initially, neither brass poster types nor brass bookbinding fonts seem to have been cast in Germany from foundry-type matrices. Instead, master slugs – rows of letters – were pressed into sand to create matrices into which molten brass could be poured. After being cast, the resulting brass form had to be worked down and polished by hand and machine. Individual sorts could then be sawed off from the slug, one by one. Fonts of brass types contained far fewer characters than a minimum foundry-type delivery. Brass fonts had a longer lifespan than foundry types, and both brass-type varieties were much more expensive than foundry-type or wood-type fonts. In many cases, the “master slugs” used in the sand-casting process must have been rows of foundry types acquired from various typefoundries.

By some time in the 1890s, the Krefeld-based engraver Otto Kaestner seems to have introduced a different brass-type making method than the sand-casting tactic mentioned above. However, I haven’t found information suggesting that hand-casting types in brass was necessarily something that Kaestner invented. According to one of his catalogs, Kaestner cast brass types from copper matrices, like typefoundries did with their “lead” types. While Hugo Friebel made large-sized brass types for poster printing, Otto Kaestner’s types seem to have been primarily smaller. He aimed them at bookbinders. A 1942/43 article in Der Buchbinderlehrling by Heinrich Lüers – probably an employee at Dornemann & Co. in Magdeburg, which acquired Kaestner’s brass-type business in the 1920s – explained the matrix-casting method for making brass bookbinding fonts. Sorts were cast from foundry-type style matrices in hand moulds, in not casting machines. That was probably because the brass-alloy used had a melting point of 1000° Celsius. Lead-based type metal melts at about 300°. Just like “lead” type cast in a hand mould, hand-cast brass sorts required several manual-finishing steps before they could be shipped to customers.

In Germany, I’d currently propose that German brass-type casting as an industrial activity seems to have been practiced for about 125 years. We could place its beginnings around the time when Falckenberg & Comp. began casting brass types for bookbinders around the late 1860s. While brass type for bookbinders is still made today, I think that the sorts are machine-milled. The other bookend on brass-type casting’s industrial era in Germany can be probably be placed around the time when the Magdeburg-based Prägeschriften und Gravuren GmbH closed in 1992. Today, the Maison Alivon in Paris claims to be the last brass-type foundry in the world. This may be accurate; I can well imagine that they still cast their letters from matrices while all other producers mill theirs instead.

Otto Kaestner: Krefeld, the man, and the firm

In 1854, Otto Kaestner was born in Magdeburg. As a boy, he was probably apprenticed to an engraver. He moved to Krefeld in 1876, perhaps following an older brother or another close relative. Between 1865 and 1868, a Carl Kaestner from Magdeburg had arrived there, too. Carl Kaestner initially worked in Krefeld as a typesetter, but by 1871 he owned his own printing business. While I cannot find evidence that Carl Kaestner (1846–1910) and Otto Kaestner ever lived at the same Krefeld address, they had the same last name, moved across the country between the same two cities, and worked within the same broader industry. That strikes me as too many similarities to be a coincidence. Krefeld is 400 kilometers to Magdeburg’s west.

The Magdeburg engraving company of Ries & Comp. had an employee named Kästner in 1839. Otto and/or Carl Kaestner may have been descended from him. Or, at the very least, they may have been his relatives. According to Friedrich Bauer’s Chronik der Schriftgießereien (1928), Albert Falckenberg became Ries & Comp.’s sole owner in 1842. The renamed Falckenberg & Comp.’s 1842 specimen, as Bauer wrote, included several polytypes for bookbinders. The letters shown on the bookbinders’ sheet may have been sold as hand-held brass stamps, rather than proper types, but the specimen is not entirely clear. Thirty years later, the Falckenberg business was renamed again, after Feodor Schmitt. In the 1870s and ’80s, the company seems to have transitioned from casting foundry type for printers to manufacturing brass type for bookbinders. Perhaps Otto Kaestner apprenticed as an engraver at the Falckenberg/Schmitt business and even learned how to sand-cast brass types there before bringing that knowledge to Krefeld and striking out on his own there.

Otto Kaestner first shows up in Krefeld’s 1878 address book – a whole decade after Carl – where he was one of seven engraving businesses then active in the city. On some occasions, Otto and Carl Kaestner spelled their last name Kästner, but each seems to have used ae more constantly than ä. Otto Kaestner’s company publications claimed that he founded his business in 1876. That was the year he moved to Krefeld and probably when he went out on his own as an independent engraver.

Kaestner’s address-book listings do not mention brass fonts for another decade (1888). By that time, his business definitively catered to the bookbinding market. You can see a few photographs of the materials he sold here. Around 1897, the Kaestner family and business moved to Oehlschläger Straße 67. A structure numbered 65/67 stands there today, which the city’s list of protected buildings notes as being constructed between 1897 and 1900. Both the residential area for the Kaestner family in the front and the factory in the back survived the Second World War and the decades since.

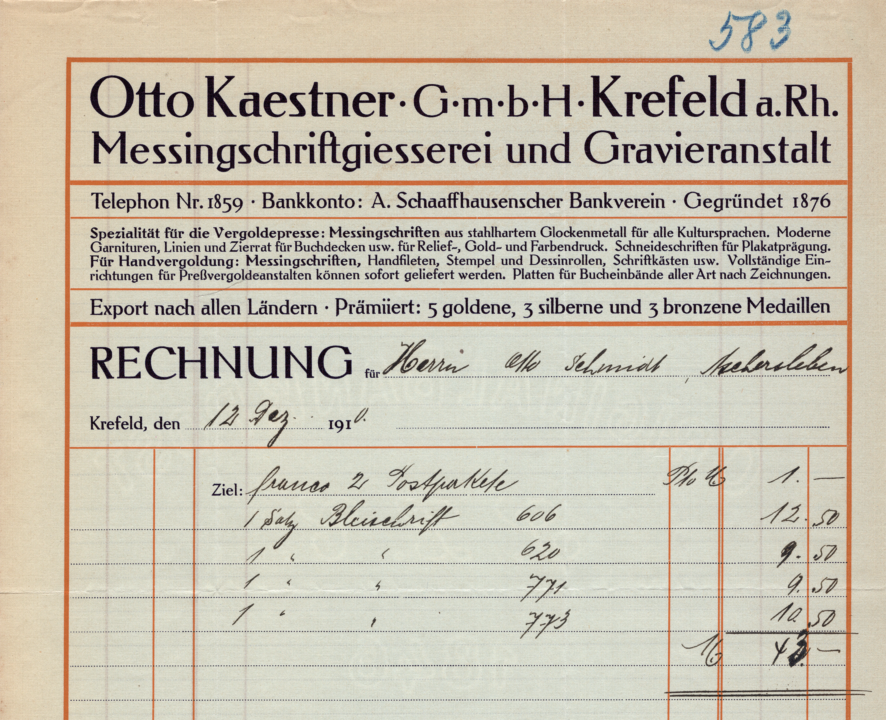

Top half of an invoice from the Otto Kaestner GmbH, sent in 1910. The invoice’s text was set in the Behrens-Antiqua fonts, from Gebr. Klingspor in Offenbach am Main. Kaestner’s company did not sell brass fonts of Behrens-Antiqua at this time. The invoice was printed by L. Schwann in Düsseldorf.

On the Otto Kaestner catalogs, advertisements, and correspondence, the company proudly listed the number of prizes it had won at international exhibitions. I haven’t yet assembled a complete list of its successes in that area, but Kaestner received silver and bronze medals at the Antwerp World’s Fair in 1885. That was followed by gold and silver medals at an 1886 Paris fair, a gold medal at an 1887 London fair, two more at the 1894 World’s Fair in Antwerp, and a silver medal at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. The German Empire’s catalog for its exhibitions at the 1900 Paris Fair include a short entry for Kaestner, but a more detailed description of the company appeared in a smaller catalog listing participating companies from the country’s book trades:

Otto Kaestner, Krefeld, Rheinland. Engraving workshop and typefoundry for brass letters. Specialty: brass type and ornaments for bookbinders. The company, founded in 1876, employs between 75 and 80 workers. It owns an electric power-generating facility, 15 machines, and a foundry for hand and press-embossed types. The company’s products are exported all over the world. [The exhibit includes] typefaces and engravings for embossing and gilding with the gilding press and by hand. They can also be used in bookbinding or the fabrication of posters, etc. Framed prints from brass types [are also exhibited].

– Katalog der Deutschen Buchgewerbe-Ausstellung Paris 1900

Kaestner’s engraving business became a limited liability company in 1906, which he owned with the sons from his first marriage, Robert and Paul Kaestner. Robert Kaestner died a year later; Paul Kaestner’s share of the company remained at about a quarter until the 1920s. With Maria Schnencke, his first wife, Otto Kaestner also had a daughter named Margaret. She emigrated to the United States with her husband but did not have a long life, dying in 1923 at age 36.

According to Friedrich Bauer’s Chronik, the rival brass-type maker Dornemann & Co. in Magdeburg purchased the brass-typefoundry portion of Kaestner’s business in 1922. Otto Kaestner seems to have retired in 1931, and he passed away in 1934. Although Paul Kaestner became the engraving business’s sole owner, company operations seem to have ceased around that time. Surviving legal records suggest that its financial situation was precarious, and Paul Kaestner was also involved in a legal dispute with his stepmother and half-sister over their inheritance. The Otto Kaestner GmbH was removed from Krefeld’s business registry in 1937.

As far as I know, brass-type production continued in Magdeburg until 1992, although I don’t know how long Kaestner’s casting methods remained in use. When Germany was divided after the Second World War, Magdeburg fell into the area controlled by the Soviet administration. That later became the GDR, whose government expropriated Dornemann & Co. During the 1970s, the company was renamed VEB Prägeschriften und Gravuren. A Magdeburg-based sign-engraving firm acquired it in 1992, and I think it still occupies at least part of the old Dornemann & Co. factory building today.

Maas & Jungvogel

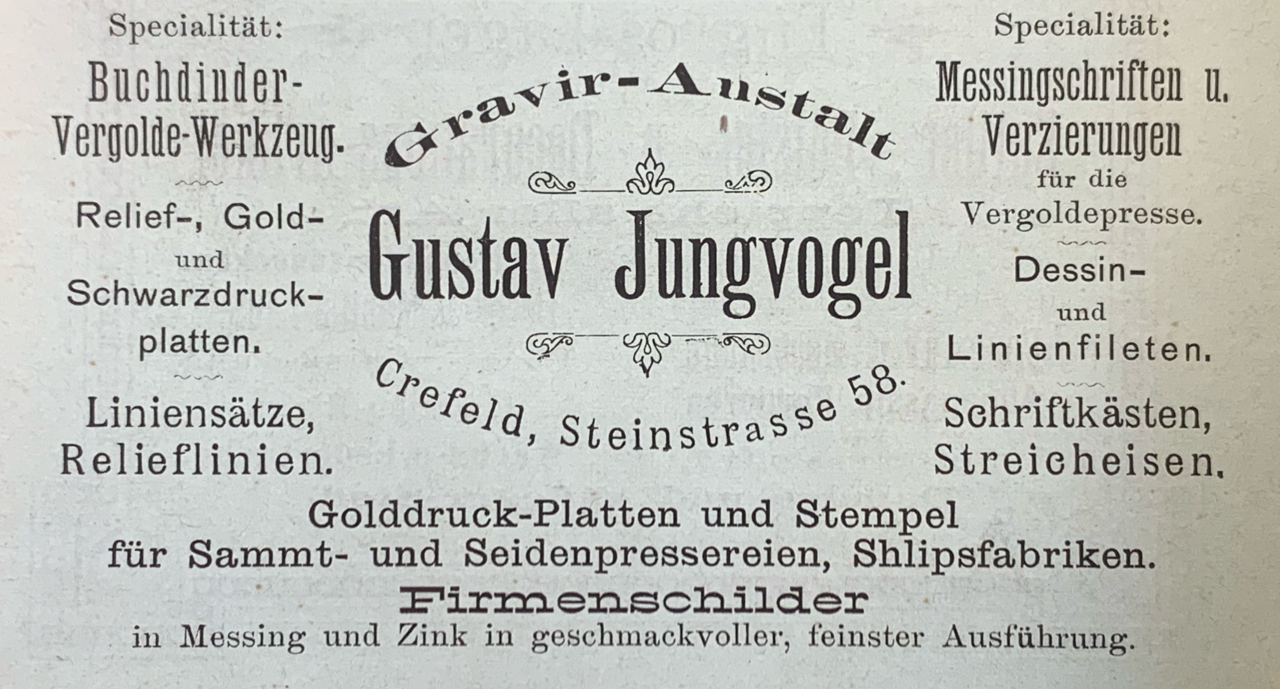

Between 1889 and 1893, the engraver Gustav Jungvogel set up a business in Krefeld making bookbinders’ tools. In 1893, he partnered with Hugo Maas. However, it seems they did not stay together long. Gustav Jungvogel became an independent engraver again soon afterward. Hugo Maas must have retained the “Maas & Jungvogel” name.

Advertisement for Gustav Jungvogel’s engraving business in a Krefeld city address book, 1893. That same year, Jungvogel had entered into a partnership with Hugo Maas, creating the Maas & Jungvogel company. Note that the first lowercase “b” in “Buchbinder-” on the top left is misspelled, with a “d” having been set instead.

Although it was not the only other engraving company in Krefeld, Maas & Jungvogel probably developed into Kaestner’s chief local competition. Before 1895, Maas & Jungvogel purchased Ad. Feik’s firm in Hamburg, which must have increased its product range considerably. Like Otto Kaestner, Maas & Jungvogel exhibited at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. With time, Maas & Jungvogel may have made more effort at participating in national and international design networks. For instance, the firm was an early member of the German Werkbund. That should come as no surprise. As the image at the top of this post indicates, Maas & Jungvogel advertised its partnerships with Peter Behrens and Gebr. Klingspor – both of which were Werkbund founders. It also highlighted its connections with “brand name” designers in its correspondence. Maas & Jungvogel remained in business until at least 1962.

What were the type designs’ sources?

Like the other brass-type foundries, Kaestner’s catalogs show a wealth of recognizable type designs easily linkable to various German and American type foundries, etc. Kaestner probably licensed the type designs it sold from type foundries. While hints at partnerships between brass-type makers and large typefoundries do not appear in Kaestner’s catalogs, they do in specimens produced by other brass-type makers. For instance, in a circa 1911 catalog from the Magdeburg brass-type foundry Dornemann & Co., pages showing typefaces from H. Berthold AG include a footer reading »Alleiniges Recht der Vervielfältigung« or “sole reproduction rights” [my translation]. No such metatext appears on pages showing D. Stempel AG type designs. Meanwhile, in an undated specimen from the Leipzig brass-type maker R. Gerhold, that company claimed an »Alleiniges Recht der Herstellung« [sole right of manufacture] for certain Stempel, Bauer’sche Gießerei, and Gebr. Klingspor designs.

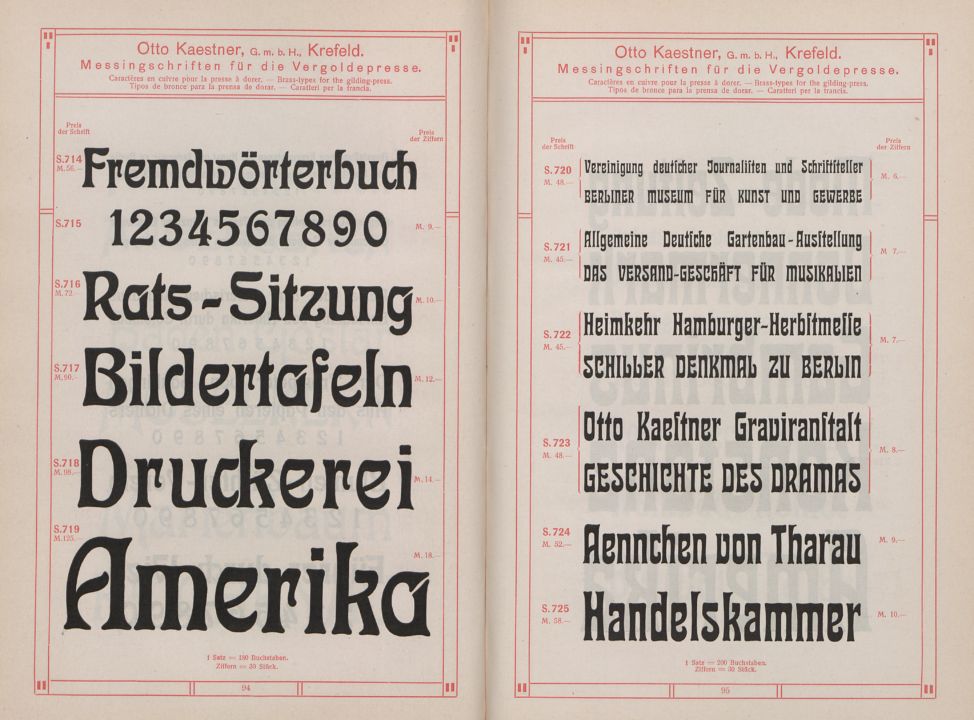

Pages from a circa 1910 Otto Kaestner GmbH catalog showing brass-type versions of two D. Stempel AG typefaces. On the left is Stempel’s Halbfette Künstlerschrift. Schmale fette Künsterschrift Wodan is on the right. Both were designed for Stempel by F. Schweimanns in Hannover. Kaestner’s specimen does not attribute the designs to anyone – neither Stempel nor Schweimanns. Source: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, call number 50 MB 5415.

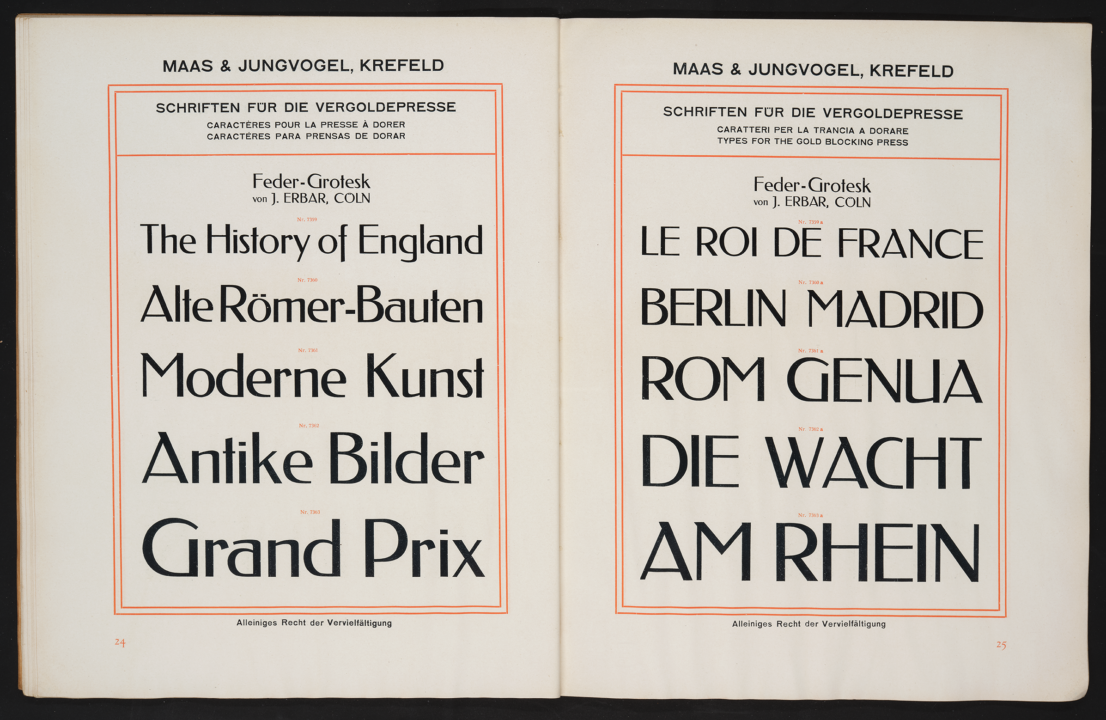

Our zine reproduces part of a 1910 invoice from Kaestner’s company (you can see the whole print on Fonts In Use). Its text was typeset in various sizes of Peter Behrens’s Behrens-Antiqua typeface, produced by Gebr. Klingspor in Offenbach am Main three years earlier. Yet, while Kaester used Gebr. Klingspor typefaces like Behrens-Antiqua in his advertising, he was not selling brass-type versions of them to customers. Instead, his Krefeld-based competitor Maas & Jungvogel seems to have had the exclusive right to sell brass versions of Behrens-Antiqua and several other Gebr. Klingspor typefaces. Maas & Jungvogel must have also had a relationship with Ludwig & Mayer, through which they had an exclusive right to sell brass-type versions of at least some of that foundry’s typefaces. This seems to have continued for some time as well. Decades later, for instance, Maas & Jungvogel sold the brass-type versions of Erbar-Grotesk, the Ludwig & Mayer foundry’s geometric sans serif typeface designed by Jakob Erbar in Cologne.

Two pages from an undated Maas & Jungvogel catalog with brass-type versions Ludwig & Mayer’s Feder-Grotesk typeface, designed by Jakob Erbar in Cologne. While the specimens mention the typeface’s designer, they do not attribute it to Ludwig & Mayer explicitly. Nevertheless, the text at the bottom of each page (Alleiniges Recht der Vervielfältigung) imply that Maas & Jungvogel had an exclusive arrangement with the Ludwig & Mayer typefoundry. Source: Allard Pierson, University of Amsterdam, call number KVB LPF 215.

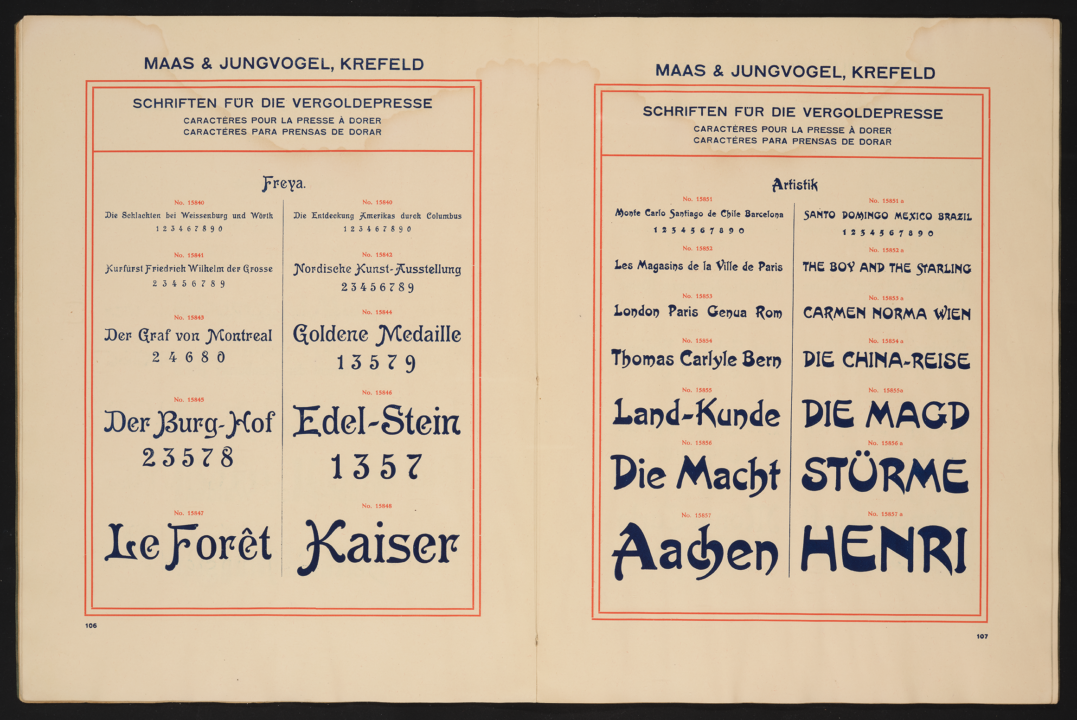

Pages from an undated Maas & Jungvogel catalog showing brass-type versions of the Rudhard’sche Gießerei’s Freya typeface and H. Berthold AG’s Artistik. Source: Allard Pierson, University of Amsterdam, call number KVB LPM 1895.

Brass-type foundries created their own type designs, too, at least occasionally. An undated specimen from L. Berens in Hamburg features an art-nouveau-style typeface in several sizes called Niederelbe. The specimen claims that this was an in-house design, which L. Berens had filed with the design registry for a patent. And a ca 1910 Dornemann & Co. specimen includes several typefaces that it may have created. These include a Französische Antiqua, a Schmale Antiqua, a Moderne Antiqua, a decorative serif named Bavaria, a sans called Lipsia-Grotesk, another sans called Breite Grotesk, a Secession-like sans called Saxonia-Grotesk, an all-caps design called Tip-Top, an italic called Mercantil-Grotesk, a script called Halbfette Anglaise, and another called Excelsior.

In the German central government’s Deutscher Reichsanzeiger newspaper, one finds quite a few notices of design patent registrations made by Otto Kaestner between the 1890s and the 1920s. Nevertheless, these seem to be for ornaments rather than typeface designs. Translated into English, a typical notice reads – like two published on 9 December 1907 – reads:

No. 1695. Otto Kaestner G.m.b.H. in Crefeld, an envelope sealed with two business-seal impressions containing one design for book-printing ornaments, surface products, business number P 3400, protection period [granted for] 3 years, registered on 7 November 1907, at 11:30 in the morning.

Kaestner probably produced a number of small specimen brochures for his company’s ornaments and border-printing elements. The Deutsches Technikmuseum in Berlin has a brochure for his company’s P 3400 series.

More Krefeld brass-type makers

- In the 1890s (at least), a Krefeld engraver named August Storde was likely also producing brass types. I suspect that these were a less-significant part of his product portfolio than brass types were for Otto Kaestner or Maas & Jungvogel.

- In 1898, one of Kaestner’s employees went out on his own. According to his announcement in the Allgemeiner Anzeiger für Buchbindereien, Joseph Maass [also spelled Josef Maaß, Josef Maas, etc.] had been the chief draftsman and engraver at Otto Kaestner’s firm. As far as I could determine, Jospeh Maass was not related to Hugo Maas from Maas & Jungvogel.

- Richard Niescher’s bronze-engraving workshop also produced type for bookbinders’ gilding presses, at least according to a 1909 announcement from the company.

What’s next?

Over the next six months, I hope to accumulate additional information on the brass-type industry. So far, the list of companies I’d like to investigate includes:

- L. Berens, Hamburg

- Brandt & Co., Leipzig

- Dornemann & Co., Magdeburg

- Ad. Feik, Hamburg

- Hugo Friebel, Leipzig

- Gerhardt & Teltow, Leipzig

- R. Gerhold, Leipzig

- Hugo Horn, Leipzig

- Otto Kaestner, Krefeld

- Edmund Koch & Co., Magdeburg

- Joseph Kreuter, Giessen

- Maas & Jungvogel, Krefeld

- Gebr. Mejo, Leipzig

- Max Orlin, Leipzig

- B. Sorger, Bremen

- Weißbeck & Röder, Leipzig

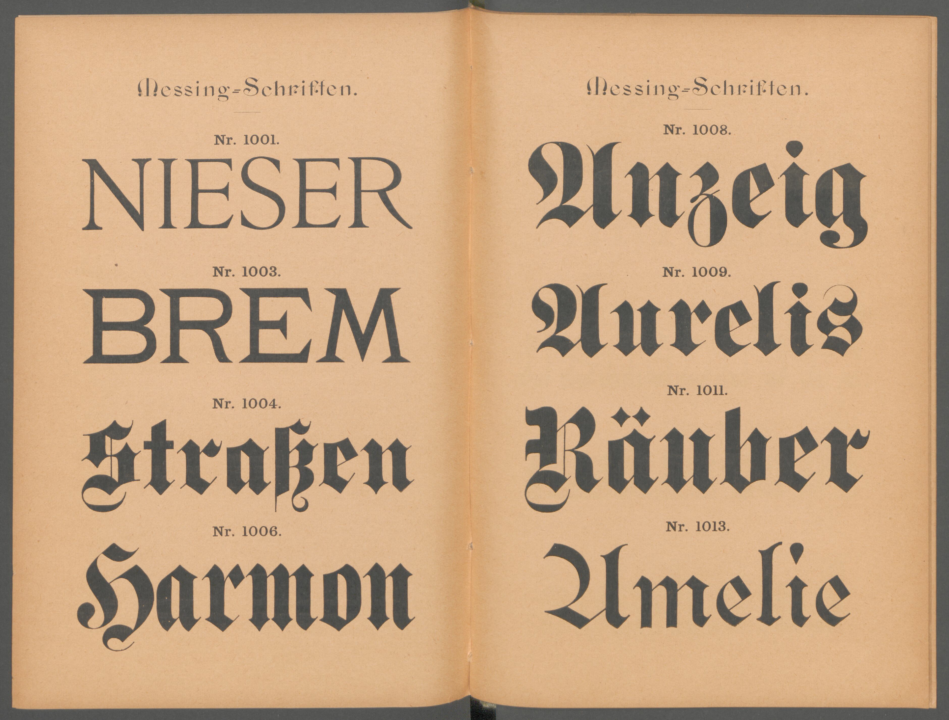

Two pages of brass poster types from a catalog of the J. H. Rust & Co. typefoundry in Vienna. These were likely created through the method introduced by Hugo Friebel in Leipzig during the 1880s. Source: Stiftung Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin, Historisches Archiv III.2-24194.

Proper typefoundries like J. G. Schelter & Giesecke, of course, also produced brass types for sale to bookbinders and poster printers. I am not sure whether I should include their offerings in this project yet. While I assume they would have used Hugo Friebel’s manufacturing methods, I do not know that in each instance.

I am not entirely sure what happened to Hugo Friebel & Co. In the Chronik der Schriftgießereien, Friedrich Bauer indicates that Dornemann & Co. bought the factory, sometime between 1905 and 1914. Earlier in this article, underneath my caption for the Hugo Friebel specimen page, I mentioned Wilhelm Jacob’s 1905 article on brass-type manufacture from Klimsch’s Jahrbuch. In that article, Jacob wrote that Friebel sold his brass-type-making method’s patent to the Leipzig-based A. Numrich & Co. typefoundry. In an 1893 notice, Numrich & Co. announced that it had purchased Hugo Friebel & Co.’s machines, utensils, and models [i.e., sandcasting patrices], as well as the company’s design patents. Numrich & Co. was eventually acquired by the Bauer’sche Gießerei in Frankfurt. I do not know if the Bauer’sche Gießerei continued to make brass types after closing the Numrich & Co. factory down in 1927.

According to Friedrich Bauer, the J. H. Rust & Co. typefoundry in Vienna also used Friebel’s brass-type making methods. While H. Berthold AG purchased that foundry in 1905, I don’t think Berthold retained Rust & Co.’s brass-type products. Instead, Berthold sold large-sized steel ferrotypes manufactured on behalf of the foundry by Dornemann & Co. My next post in this series is devoted to those ferrotypes. The wealth of brass rules, brass borders, and other brass elements produced by Berthold and similar companies for the letterpress printing market will not fall within this project’s scope.

Another foundry that Berthold acquired in the twentieth century was Julius Klinkhardt’s. Some Klinkhardt specimens include pages displaying large brass types, presumably for poster printing. However, it is conceivable that Klinkhardt’s foundry didn’t manufacture them but rather was selling them on behalf of one or more Leipzig-based brass-type makers.