This is a post about a pantographic engraving machine I cannot find a picture of – the “Ludwig–Hofer pantograph.” Nevertheless, I think it could be an interesting missing piece of the historical puzzle surrounding the introduction of pantographic engraving machines in typefounding. In the United States, makers of wood type fonts had already begun using pantographic engraving to manufacture their products in the 1830s. Several decades passed before pantographic engraving made the jump to foundry type. Looking for information on typefoundry adoption of pantographic punchcutting methods, you can’t help but read about Linn Boyd Benton’s pantographic punchcutting machines, in-use from the 1880s onward. Benton’s pantographic punchcutting devices were vertical machines. Operators placed a pattern at the machine’s bottom, and a smaller punch was cut somewhat higher up in the device. Older wood type pantographs were horizontal machines. On one side of the device, a pattern was traced. A wood-type sort was cut on the other. As far as I know, most – if not all – typefoundry matrix-engraving devices were also horizontal machines.

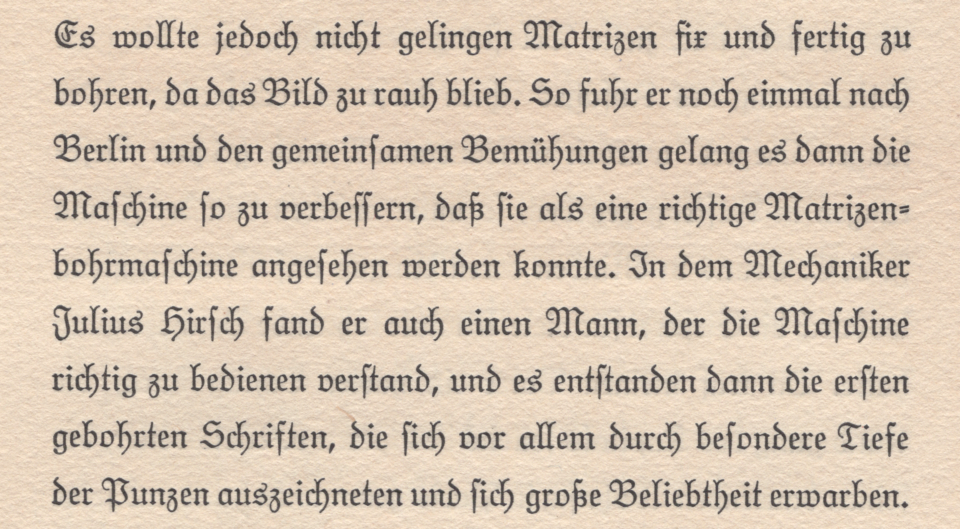

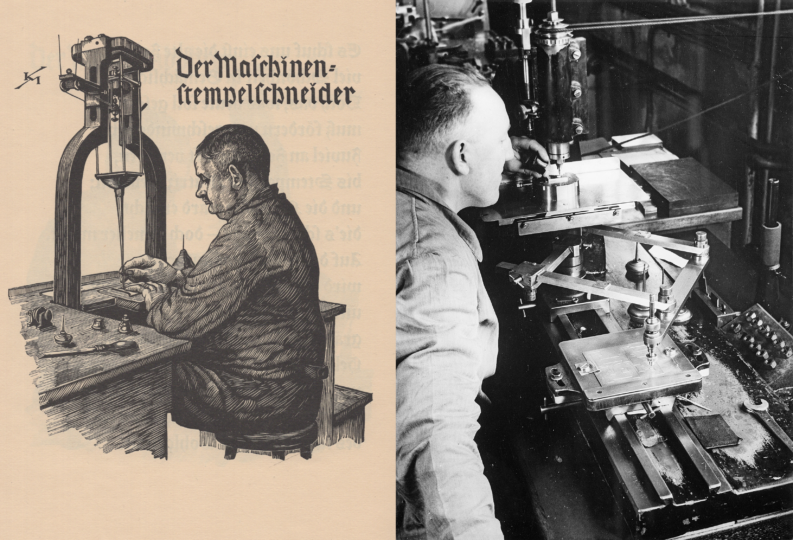

The woodcut on the left shows a worker pantographically engraving a punch with a Benton-style vertical machine. Reproduced from Karl Mahr’s Der Druckbuchstabe (Offenbach am Main: Verein Deutscher Schriftgießereien e.V., 1928). The photo on the right shows a worker operating a horizontal matrix-engraving machine at D. Stempel AG in Frankfurt am Main, circa 1935. He seems to be engraving a fette russische Memphis matrix. sdtb/ Foto: Hist. Archiv.

Germany’s first matrix-engraving machine. Probably.

The first pantographic engraving machine pre-dating Linn Boyd Benton’s device David M. MacMillan mentions on Circuitous Root is a model the Cincinnati Type Foundry imported from Germany in 1880. The machine seems to have been a failure there, so Cincinnati sold it to the Central Type Foundry in St. Louis, who did manage to use it effectively. MacMillan provides more details about the machine here. Although it is not clear where in Germany the Cincinnati Type Foundry procured the matrix engraver from, a machine we could call the “Ludwig–Hofer pantograph” seems like a good candidate to me. Developed in Berlin by a Mr. Hofer for the Frankfurt typefoundry owner Jean Noé Carl Jakob Ludwig (1843–1926), this is the earliest German-made matrix-making machine I am aware of.

In his 1955 book, Das tätige Frankfurt, Franz Lerner stated that Ludwig’s foundry was the first in the world to cast type from [pantographically] engraved matrices. You can read excerpts from his book here; to find the relevant passaged, just search for “Ludwig.” For the moment, I can’t say for sure whether or not that claim is correct. If you know of a typefoundry anyway in the world that mechanically engraved matrices before the 1870s, please let me know.

Until 1875, Ludwig had been a manager at Frankfurt’s Flinsch foundry. Just before Christmas Day in 1875, he set up his own business. Early specimens from his foundry bear the name “C. J. Ludwig.” In 1883, the salesman Ludwig Mayer joined the company as a partial owner. The foundry rebranded as Ludwig & Mayer. It stayed in business under that name until closing more than a century later, in the mid-1980s.

Developing the “Ludwig–Hofer pantograph.”

So far, I have only found one German source discussing the “Ludwig–Hofer” pantographic matrix-engraver’s creation in any detail. In 1926, Ludwig’s son Richard published a short chronicle of the Ludwig & Mayer typefoundry’s first fifty years. Published by the foundry in an edition of one thousand, he simply titled it 1875–1925. The book has no page numbers, but one spread discusses the pantograph. I have translated that spread’s text below.

After 1876 – C. J. Ludwig’s first full year in business – he aspired to publish new good products original to his foundry:

Because even then, the printer always wanted something new, just like today. Given the high costs associated with cutting a product, however, he had to be very cautious. As he had limited resources, he looked for a way to make production cheaper. One day, he found an engraver named Kurz, who worked in the Katharinenpforte, using an engraving to engrave seals [Petschafte]. It occurred to him that this machine could be used for engraving matrices. He traveled to Berlin, where this engraving machine was manufactured by the mechanical engineer Hofer. There, he spent three weeks learning to operate the machine and traveled home full of ideas after ordering a machine modified according to his specifications. When he had this machine, he secretly made the first attempts to engrave matrices together with an engraver named Mandel in an attic of his small factory building.

However, they could not succeed at engraving matrices completely because the image remained too rough. So he went back to Berlin and, working together [with Hofer], then succeeded at improving the machine so that it could be seen as a real matrix-engraving machine. He found a machinist named Julius Hirsch who could operate the machine correctly, and the first [pantographically] engraved fonts were thus developed, which were characterized above all by the particular depths of their counters and which became very popular. Other typefoundries subsequently acquired this engraving machine, and it is still in use today [1925] in the same – or slightly modified – form. This engraving machine enabled my father to bring out new products, giving his small business more work and encouraged him to continue on the path he had taken. Only recently, the firm of Michael Kämpf in Frankfurt am Main completed the construction of a matrix-engraving machine deviating from the old Hofer machine, and Ludwig & Mayer also put the first of those into use.

Richard Ludwig’s chronicle does not include any dates for the matrix-engraving machine’s development and installation. However, as the events he related both before and after this episode each took place in 1877, I find it a safe assumption that his father’s foundry began engraving matrices during that year, too.

Is there evidence of collaboration between C. J. Ludwig and the Cincinnati Type Foundry?

I think that information about the “Ludwig–Hofer pantograph” is interesting in its own right. The question of whether or not the Cincinnati Type Foundry’s matrix-engraving machine was a “Ludwig–Hoefer pantograph” is difficult to answer. It may be easier to determine if Ludwig and Cincinnati had a business relationship with one another. If they did, Ludwig being the source of Cincinnati’s German machine is more likely.

Comparing Ludwig & Mayer and the Cincinnati Type Foundry’s catalogs could provide an idea of how large the product overlap between those foundries was. Although the University of California Libraries have digitized Cincinnati Type Foundry’s 1882 catalog, I’m not aware of any Ludwig & Mayer catalogs yet online. Perhaps the two foundries shared typefaces. So far, I have only compared their sans serif offerings. In my database of 19th-century sans serifs sold in Germany, there is one sans serif Ludwig & Mayer sold that might have originated in Cincinnati.