When Theinhardt purchased this house at Linienstraße 144 in 1860, he added a new building behind it. Then his typefoundry operated here for almost thirty years. After he sold the business off, his successors never changed the foundry’s name. It always retained the “Ferd. Theinhardt” name.

In 1849, Ferdinand Theinhardt (1820–1906) became an independent punchcutter and typefounder. Prior to that, he had cut punches for the in-house typefoundry at Eduard Haenel’s printing house. Some details about Theinhardt’s life and career are readily available today because of an autobiography published in 1899, about 14 years after he retired.[1] This is a long post. It covers several topics. I suspect that you’ve come to expect that much from this blog by now. Let me know on Twitter if you think I’m not doing something right!

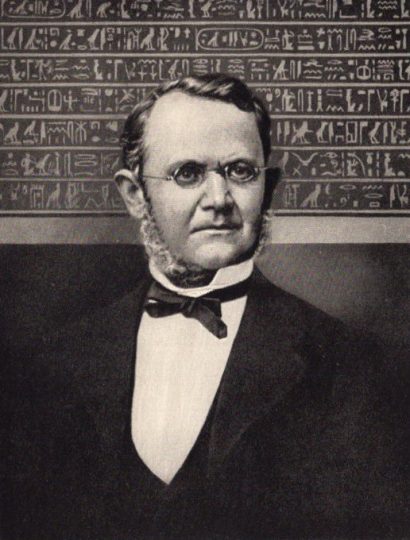

Posthumous portrait of Theinhardt from Das Haus Berthold (1921), p. 49. The book depicted him in front of a hieroglyphic text, as he cut at least 2,000 hieroglyphs for the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius. You can read more about that project in this other post.

Theinhardt was originally from the German city of Halle. Politically, Halle was part of Prussia’s Saxon province during his lifetime. In Theinhardt’s autobiography, he recounted not only starting his own business in 1849, but that he became a citizen of Berlin then, too. Although city citizenship (Bürgerrecht) may sound foreign today, in the 1840s it was typically still a necessary step for men desiring to work as independent tradesmen. Part of Theinhardt’s naturalisation involved swearing an oath of allegiance to the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, but this in no way conveyed Court Purveyor status upon him. No period sources point to Theinhardt ever having been a “royal punchcutter,” or Hoflieferant. Augustus Beyerhaus, who was Theinhardt’s predecessor when it came to the hieroglyph types with which he made his name, was indeed an “engraver to His Majesty the King of Prussia.”[2]

Ferd. Theinhardt and its early successes

In his autobiography, Theinhardt summarised the successes he enjoyed during his first year in business. He wrote:

I rented an apartment that had a small workshop. With the help of a bricklayer, I built a cast iron furnace, with which I manually cast type (at that time, Haenel only built type-casting machines for their own use). I also made matrices and cut new punches for letterpress and newspaper printing houses. A year later, the foundry had expanded, and the best printers had gradually become my customers, as well as a number of newspaper printers, including the Vossische Zeitung, the Spenersche Zeitung, the Börsen-Zeitung, the National-Zeitung, the Volks-Zeitung, the Post, the Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, also the German newspaper of St. Petersburg, the Germania, the Schlesische Zeitung, and others.[3]

During the 1840s and ’50s, Haenel’s printing house was just outside Berlin’s city borders, near where Potsdamer Straße and Lützowstraße intersect today. The apartment that Theinhardt wrote about, however, was probably inside the city proper. If he did not immediately move in 1849 into the area that was then part of Berlin’s northern section, he would have soon done so soon afterwards. Berlin’s address books included listings for the city’s typefoundries, and Theinhardt’s foundry was first mentioned in the Adreßbuch for 1851. The location given was Linienstraße 117. Perhaps that was the building housing the apartment Theinhardt mentioned above?

Theinhardt ran his foundry until 1885. For all that time, it remained in the Linienstraße – just not always at the same address. For instance, the 1856 address book put the foundry at Linienstraße 118, only for it to be listed at Linienstraße 117 again from 1857 to 1860. Then, Theinhardt bought a house at Linienstraße 144. He lived in that house until the late 1880s, and the foundry was in the building until 1888/89. This house still stands today, in Berlin’s Mitte district. It is not far from the U-Bahn station Oranienburger Tor or the S-Bahn station at Oranienburger Straße.

The house that Theinhardt bought

As I mentioned in this series’s post on the Norddeutsche Schriftgießerei’s factory in Friedrichshain, buildings constructed around a central courtyard are a common feature of Berlin architecture. The street-facing parts of a structure or building complex would typically be residential units – perhaps with a store, restaurant or a bar on the ground floor, too – while some of all the units in the back could be given over to industry. So it was with Linienstraße 144: the front was residential, but there was room for a workshop in the back (now, at least some of the tenants in the front seem to be businesses; one is a museum). While larger Berlin typefoundries like Berthold and Gursch occupied factory buildings that had been purpose-built for them, much of the Linienstraße 144 house was already in place when Theinhardt purchased it. The oldest parts date back to 1794. Today, the entire site is a historic landmark.

The structure on the left-hand side of the above photograph was probably built by Ferdinand Theinhardt in 1860, or just afterwards. It is likely where the Ferd. Theinhardt typefoundry would run from, between that date and 1888/89, when they relocated to Jerusalemer Straße. In the photograph’s background, you can see the rear of the 1794 house, whose front is pictured at the top of this post.

According to Berlin’s landmark commission website, the street-facing building and the east wing behind it went up first, at the end of the eighteenth century. Being older than its neighboring buildings today, Linienstraße 144 looks relatively short. It has just two storeys instead of four. At some point before Theinhardt acquired the house, two subsidiary structures – a stable and a depot – had gone up in the back, on the western side of the courtyard. In 1860, Theinhardt bought the house and replaced the stable and the depot with a new four-storey building, which would adjoin to the main house. This new building was probably where his foundry would have operated from.

The five-storey factory on the south end of the Linienstraße 144 courtyard, on the other hand, only went up in 1889, after both Theinhardt and his former foundry had moved away. It would not have been built for them. The Linienstraße 144 buildings were renovated in the 1990s, but at least some original features are still present, especially in the front house and the not-Theinhardt factory building in the rear.

The other foundries at Linienstraße 144

In 1885, Ferdinand Theinhardt sold his typefoundry off to Oskar Mammen and two brothers, Robert and Emil Mosig. The Linienstraße 144 buildings were sold in 1888. By 1889, both the Ferd. Theinhardt typefoundry and Ferdinand Theinhardt (the man) had each moved out.

Photograph of the courtyard at Linienstraße 144, looking south. The street-facing house is not in the picture (it was directly behind me when I made this shot). The white building to the left probably dates from 1794, while I believe that Theinhardt added the white building on the right in or about 1860. In 1889, the property’s new owners had the brick building in the background erected.

After that move, Theinhardt and his former foundry went their separate ways. By this I mean that they moved to different geographic locations within the city, separated from one another other by a bit of distance. He and the company were no longer direct neighbors. But the company never renamed itself. Until Hans Schweitzer sold the foundry off to H. Berthold AG in 1908, the business continued to run under the name “Ferd. Theinhardt.” Berthold kept the Theinhardt foundry operating as a subsidiary after that, too.

According to the U144 Untergrund Museum, who occupies the street-facing house’s basement, there were more foundries on the premises after Theinhardt left. However, those foundries weren’t type foundries. For decades, at least some of the various companies who worked in parts of the factory building (and perhaps other houses’ units, too) cast metal signs and other relief items. Although I do not know exactly when this kind of casting began, it continued through 1995.

That work was undertaken by generations of East German Volkseigene Betriebe (Peoples’ Own operations), as well as by the post-reunification companies S&M Schilder und Reliefgießerei Berlin GmbH/S&M-Schwidder-Gießerei und Schilder GmbH. Both the branding for the house today (the Berlin design studio Naroska has repackaged it as L144 – Die Gießerei) and the U144 present Linienstraße 144 as a place where metal has been cast continuously since 1860. That is certainly interesting.

Retirement? Looking for meaning in typespecimen paratext

Exactly when Theinhardt stopped all work with his (former) foundry is not clear. In the notice of the foundry’s sale that ran in an 1885 issue of Archiv für Buchdruckerkunst und verwandte Geschäftszweige, the journal’s editors stated that Theinhardt would continue to play a role in the business (»Herr Theinhardt wird seine Thätigkeit auch noch ferner dem Geschäft widmen«). Yet, in his autobiography, Theinhardt made no mention of continued work with Mammen and the Mosig brothers. Instead, he wrote that he filled his time with drawing and painting until his wife’s death in 1894, after which he had no desire left for work of any kind (»An Tätigkeit gewöhnt, zeichnete und malte ich bis 1894, wo der Tod meiner guten Frau mir alle Lust zur Arbeit raubte.«).

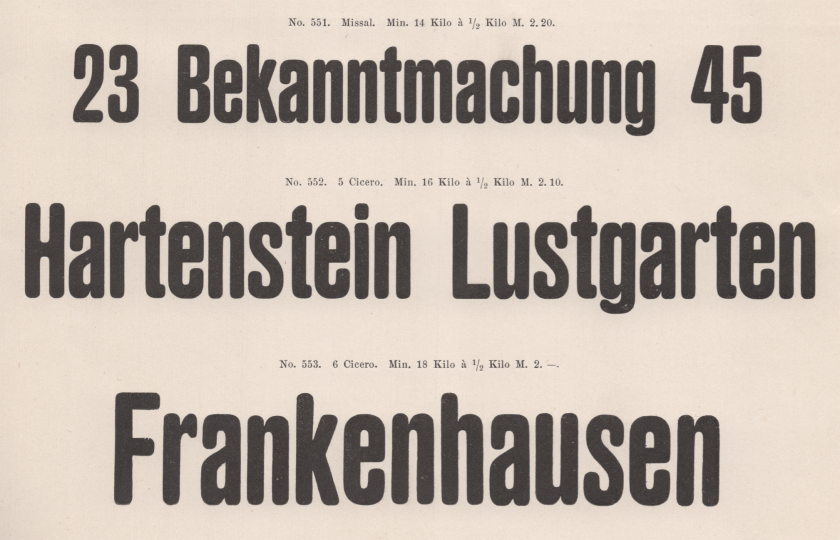

48, 60, and 72 pt fonts of the Ferd. Theinhardt foundry’s Neuste schmale fette Zeitungs-Grotesque typeface, as shown in a supplement to the January 1886 issue of Archiv für Buchdruckerkunst und verwandte Geschäftszweige. I have not yet found a source that attributes the design or the punchcutting of this type to any specific persons. Although it is possible that Ferdinand Theinhardt himself could have been behind them, I find it as equally likely that he was not.

As I mentioned in a talk at the Berlin State Library, the Ferd. Theinhardt foundry published the first sans serif design it had produced entirely in-house in or just before January 1886.[4] This typeface, originally named Neuste schmale fette Zeitungs-Grotesque, and renamed Enge fette Grotesque a few years later,[5] had rounded stroke endings. It bears no stylistic resemblance to Akzidenz-Grotesk, and it was never incorporated by Berthold into that family, either.

Perhaps the Neuste schmale fette Zeitungs-Grotesque was cut by Theinhardt himself. I have found no sources that either confirm or deny this. If he did cut its punches, though, it was almost certainly the only sans serif he ever would have worked on. The other two sans serif typefaces that appeared in Theinhardt’s specimens before 1886 were designs that had originated at other foundries, as I illustrated in the Berlin State Library presentation I linked to above.

The foundry published the typeface as part of a duo. Its slab serif variant’s name was Neuste schmale fette Zeitungs-Egyptienne. You can view each page in full on Flickr [here] and [here]. A notice appears at the very bottom of each of those pages, reading that »die kleineren Grade, sowie 7 und 8 Cicero, sind im Schnitt und folgen nach« (the smaller sizes, as well as 7 and 8 Cicero [84 and 96 pt] are being cut and will follow). That neither of these typefaces were finished in late 1885/early 1886 – at least in terms of their full range of sizes – suggests to me that these are likely not the work of Ferdinand Theinhardt himself. Or at least not entirely.

A line of text at the top of each sheet is written in the first-person singular: “original creation of my house.” However, I do not see this as an indication that the types were cut by Ferdinand Theinhardt (the man). Instead, the typefoundry is speaking here as a singular unit. This was not uncommon. I have seen other German foundries do this, such as in a circular from C.F. Rühl, after Mr. Rühl had been dead for about 15 years.[6] This first-person singular is the three new owners of the Ferd. Theinhardt foundry – and their employees – speaking with one corporate voice.

A local printing office named R. Gensch printed the specimen sheets displaying this pair of type designs. Although the printer set their credit in very small type at the bottom-right corner of each sheet, it is still an important detail for us today: it indicates that the Theinhardt foundry had no printing facility inside of its foundry in 1885/86. Although I do not have exact details at my fingertips, I seem to recall that several large German typefoundries did not establish printing divisions until the 1890s, or even the twentieth century, so this is not surprising. Nevertheless, I find it an important detail to indicate here.

As type designers and typographers, the actual designed letterforms on type specimen sheets are often what we concentrate on the most. While I’m not advocating that we shift our emphasis, we should not ignore the other information printed on them. This paratext is often rich with detail.

I have read speculation by some designers that Theinhardt – as an old man in his late 70s or early 80s – might have theoretically come out of retirement during the 1890s or early 1900s to cut the punches for Akzidenz-Grotesk or Royal-Grotesk, as a freelancer for Berthold (!). I cannot find any historical evidence to support that hypothesis. As Indra Kupferschmid has blogged, no evidence was ever presented linking Theinhardt to those typefaces, before Günter Gerhard Lange incorrectly claimed in 1998 and 2003 that there had been a connection.

During the 1920s, at the very latest, Berthold celebrated Theinhardt as one of the many illustrious figures from its greater corporate past. How was this manifested?

- Berthold republished Theinhardt’s autobiography in 1920.

- They included a portrait of Theinhardt and a profile of the Theinhardt foundry in their 1921 company history, Das Haus Berthold.[7]

- For Berthold’s circa 1926 reissue of Theinhardt’s Monumental typeface – under the new name Klassik – they created a specimen book presenting him as its designer.[8]

If Theinhardt had played a role in the design of any part of the Akzidenz-Grotesk family, Berthold would have mentioned that in at least one of those publications. It would have been good PR. While they did not always explicitly credit him in the specimens, Berthold continued to sell several of Theinhardt’s academic types for decades. Probably even at late as the 1970s.

The southwesterly moves of the Ferd. Theinhardt typefoundry

Beginning in 1886, Berlin’s address books listed the Theinhardt foundry under its then-new ownership. That year’s entry read: »Ferd. Theinhardt Schriftgießerei, Schriftgießerei u. Buchdruckerei-Utensilien, N Linienstr. 144 Pt. (FA) Inh. E. u. R. Mosig u. O. Mammen«. In 1887, the foundry’s address was given as Linienstraße 123, but the 1888 and 1889 books listed the Linienstraße 144 address again.

Once the foundry left the Linienstraße, they would work from three successive locations until Berthold acquired them in 1908. First, they moved into Jerusalemer Straße 66, in what was then Berlin’s southwestern district (today, this is still part of Mitte). That address appeared in the 1890 through 1896 Berlin address books.

I don’t know when Emil Mosig left the company. He was only listed as a co-owner of the foundry in address books through 1892. By the time that the typefoundry moved again, it only had two owners: Oskar Mammen and Robert Mosig. From 1897 through 1905, address books listed the foundry as having operating in Schöneberger Straße 4. At the time, this was also part of Berlin’s southwestern district (today, it is in Kreuzberg). Its address would have put the foundry just across the street from the Anhalter Bahnhof train station.

In an 1899 profile of the foundry from Deutscher Buch- und Steindrucker, Mammen and Robert Mosig are each still mentioned as the company owners. But soon thereafter, Mammen (1859–1945) must have left the firm. He was replaced by Hans Schweitzer, who first appears as a co-owner in the 1902 address book, together with Robert Mosig. In 1907, Robert Mosig would retire from the company himself. He then promptly died. That left Schweitzer as the foundry’s sole owner. He was the one to sell the firm to Berthold. I’d like to thank Florian Hardwig for providing me with the three of the links in this paragraph. Florian also suggested that Mosig’s death could have played a role in Schweitzer’s decision to sell the foundry. Good point!

A few years before that sale, the company moved southwest again. This time, they left the city proper, and went into Schöneberg. Still independent at that time, Schöneberg would be incorporated into Berlin in 1920. In the 1906 through 1908 address books, the Theinhardt foundry’s address was given as Feurigstraße 55b. The 1909 and 1910 address books listed them as being at house number 54. As I wrote in a post last year, that is quite close to where Alphabet Type and LucasFonts each do business today.

Acquisition by the H. Berthold AG

In 1908, after Berthold acquired the Theinhardt foundry, they reorganised it as a limited liability company. This small detail is important, because any type specimen with the name “Ferd. Theinhardt Schriftgießerei G.m.b.H., Berlin” was printed after the company had become a Berthold-owned subsidiary. The foundry’s final type specimen catalogue included a number of typefaces from Berthold that Ferd. Theinhardt could then offer its customers, too.[9] The managing directors of the “Ferd. Theinhardt Schriftgießerei G.m.b.H., Berlin” were Hans Schweitzer, Otto Krause, and Gustav Mohr – at least according to the Berlin address books printed in 1909 and 1910.

In 1910, the Theinhardt foundry ceased to be a corporate entity with its own facilities. Berthold moved the subsidiary’s effects into its main Berlin factory at Belle-Alliance-Str. 87–88. That factory still stands today; it is now the Mehringhof in Kreuzberg. 1911 and 1912 issues of Berlin’s address books only listed Krause and Mohr as Theinhardt’s managing directors. The Theinhardt foundry did stay in city address books all the way through 1931, but I suspect they were just one of many companies whose names were “on the mailbox” at Berthold. According to the 8 January 1935 issue of the Deutscher Reichsanzeiger newspaper, the Ferd. Theinhardt GmbH officially closed on 21 Dezember 1934.

While I do not know what happened to Theinhardt’s staff, I suspect that at least some of them could have continued working for Berthold after 1910. Or perhaps the situation was like that of ITC’s after Monotype acquired them in 1999. For years afterwards, there was a Monotype-run itcfonts.com website, even though Monotype had no real “ITC” employees.

Ferdinand Theinhardt, the man

And what about Ferdinand Theinhardt himself? Where did he go? In Berlin’s 1886 address book, he is listed for the first time as a Rentier (retiree), living at Linienstraße 144. That’s how he appeared in the 1887 and 1888 directories, too. Like his former foundry, he also headed southwest as he moved. The 1889 address book had him living at »SW Königgrätzerstr. 95. Pt.« The “Pt.” probably stood for Parterre – from the French par terre – meaning a ground-level apartment. Today, the Königgrätzer Straße is Berlin’s Stresemannstraße.

The 1890 through 1895 address books all listed Theinhardt as having lived at that Königgrätzer Straße 95 address as well. He had no entry in the 1896 address book. Then, from 1897 through 1907, he was listed as living at Königgrätzer Straße 76. The 1908 and 1909 address books listed him at Eisenacher Straße 84.

Berlin is a funny place. A few weeks ago, I ordered the issue of the Archiv für Buchdruckerkunst that the Neuste schmale fette Zeitungs-Grotesque specimen shown above was featured in. It couldn’t be delivered to me in the office, and was left at a kiosk. The kiosk was at Eisenacher Straße 84 … the building in which Theinhardt may have died.

For those who want to believe that Theinhardt continued to play a role in his former foundry after he sold it: you may be dismayed by the lack of a period source pointing to him having done that, but you won’t be discouraged by Theinhardt’s retirement addresses. Königgrätzer Straße intersected with Schöneberger Straße, and Eisenacher Straße 84 is only about a 12-minute walk away from Feurigstraße 54/55b (granted: for an 85-year-old, it would probably have taken a bit longer to travel 900 meters).

Ferdinand Theinhardt died on 15 March 1906. I do not have a snappy explanation for why he appeared in Berlin address books through 1909. However, I suspect that these books were prepared in for print far in advance, and that it took some time for notice from the city’s registries to get to them, about address changes as well as deaths. I assume that Theinhardt moved into Eisenacher Straße 84 months before he died, if not even a few years beforehand.

Printed sources

- Ferdinand Theinhardt: Erinnerungsblätter aus meinem Leben. Second edition. H. Berthold AG, Berlin 1920 [available online here]. First edition printed (and published?) by Gebr. Unger at Bernburger Str. 30 in Berlin.

- Augustus Beyerhaus: A specimen of new Chinese types by Augustus Beyerhaus, Berlin, engraver to His Majesty the King of Prussia. “These new Chinese characteres are cut in steel and cast in matrices for the Chinese Mission of the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America”, 1851. At the Noord-Hollands Archief, this item has the inventory number 1767. This specimen was made for the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851, the first World’s Fair. It was printed in Eduard Haenel’s Berlin printing house.

- Theinhardt 1920, p. 11–12

- Ferd. Theinhardt Schritgiesserei (ed.): Neuste schmale fette Zeitungs-Grotesque. Type specimen sheet bundled with Alexander Waldow (ed.): Archiv für Buchdruckerkunst und verwandte Geschäftszweige, vol. 23, no. 1 (January 1886). Verlag von Alexander Waldow, Leipzig 1886. No page numbers.

- Ferd. Theinhardt Schritgiesserei (ed.): Ferd. Theinhardt Schritgiesserei. S.W. Berlin, S.W. Ferd. Theinhardt Schritgiesserei, Berlin. Undated, 1890s. No page numbers.

- C.F. Rühl (ed.): Letter to Flodoard Woldemar Freiherr von Biedermann, 12 July 1911. Bound into a volume of Rühl specimen held by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz with the call number An 1744/40. Unnumbered item following item number 25 in the volume. C.F. Rühl, Leipzig 1911

- Hermann Hoffmann: Das Haus Berthold 1851–1921. Zum 25jährigen Bestehen der Aktiengesellschaft. H. Berthold AG, Berlin 1921, p. 49 and 101–104

- H. Berthold-Messinglinienfabrik und Schriftgießerei (ed.): Klassik. Berthold Probenheft 223. H. Berthold AG, Berlin. Undated, circa 1926

- Oscar Jolles (ed.): Die deutsche Schriftgießerei. Eine gewerbliche Bibliographie. Unter Mitwirkung von Friedrich Bauer, Gustav Mori und Heinrich Schwarz. Bearbeitet von Dr. Lothar Freiherrn von Biedermann. H. Berthold AG, Berlin 1923, p. 188