Princeton Architectural Press recently published an expanded, second edition of Adrian Shaughnessy’s How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul. About a month ago, I received a free review copy. Although I had never read the first edition, published by Laurence King Publishing Ltd. London in 2005, I decided to read the book right away. I spent about a week with it. During two of those days, I was in bed with a cold. Shaughnessy got me thinking more than I had expected.

Are you looking for work and/or career advice?

Browsing in the design section of a bookstore, one is likely to find a number of advice books, like the Graphic Artists Guild Handbook: Pricing & Ethical Guidelines or The Elements of Typographic Style, as well as books primarily intended to impress or inspire readers, such as I Wonder and Touch Me There. Shaughnessy’s How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul is a mixture of both genres. For a well-selling design book, it is fortunately bereft of images; only a few photos—featuring work from the designers interviewed in the final chapter—are included at the back of the book.

At any stage of a career, finding new employment is difficult. A change in working status—e.g., moving from a design studio into freelance employment—can be fraught with complications. Many designers approach these subjects with dread, especially if they are not aware of all the different factors they should consider. As far as my own experience is concerned—and including my internships—I have been working more or less continuously since 1999. Even after all this time, there is little more that I yearn for than a good career coach, someone who I could call in specific moments confidentially. Among one’s acquaintances, it is common for every advice giver to lend different suggestions, and almost all proposals will at least partly overlap with some others.

The book is divided into the following sections and chapters:

- A foreword by Stephan Sagmeister

- Attributes needed by the modern designer

- Professional skills

- How to find a job

- Freelance or setting up a studio

- Running a studio

- Finding new work and self-promotion

- Clients

- What is graphic design today?

- The creative process: Interviews with Jonathan Barnbrook, Ben Drury, Sara De Bondt, Stephen Doyle, Paul Sahre, Dmitri Siegel, Sophie Thomas, and Magnus Voll Mathiassen

Things about the book that I really like

How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul is beneficial because it tries to avoid certain details, not just software concerns, but also details as to the kinds of work that one might do at the start of a career, whether working in a design studio, as part of an in-house team, or freelance. While the traditional graphic design challenges are the lingua franca of Shaughnessy’s text, the macro struggles that he describes speak to broader audiences; I would recommend this book to almost any sort of designer: not just graphic designers, but also industrial designers, architects, or film editors. Naturally, some chapters of will be more appropriate to different disciplines than to others.

There are many anecdotes in the book upon which I could comment, but I will only reference one of the many suggestions that struck me. On page 66, Shaughnessy writes, “This brings us to the second rule of creative recruitment … any employee who is any good will leave.” He continues in the next paragraph, where he quotes an unnamed associate, “‘People who want to have their own businesses make the best employees. Never be frightened to employ people who ultimately want to start their own studios.’” In Germany, many employers and employees alike seem relatively short sighted in this particular regard. I can think of several examples of decisions makers in German companies who are not very interested in hiring independent minded employees. In some cases, passive employees, ideally with a traditional attitude to employment, are employed, a world view in which job seekers hope to find employment at a single company for life, rather than at several companies over the course of a career. In the trade off between a lack of risk and greater potential career and personal development, job safety is preferred.[1]

I most enjoyed Shaughnessy’s advice on writing, especially his comments on editing and revising texts, as well as the liberal use of the delete key. As for Shaughnessy’s text itself, his style takes a pleasant, personal form. Reading the book, I felt as if I could hear the author’s voice. Each chapter seemed to end quickly, which may have had almost as much to do with the actual page length as with the author’s tone. Additionally, chapters are broken up into sections, which make the book ideal for reference, especially after it has been read through once. It is easy to go back and find things you thought you remembered. The content of How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul is deep enough to justifying taking it off the shelf, even if you are in a content stage of your career.

Why I never read this book’s first edition

If I am making it sound as if How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul is so commendable, one may rightfully ask why I never bothered to read the book before now. Truth be told, I likely would not have read it yet either, had the publisher not provided me with a copy. Previously, no one in my network ever recommended this book to me. I wish that someone had, though. If a trusted friend or colleague had, I may have given the book a proper look before now.

Perhaps my previous reluctance is because, by the time the first edition was released in 2005, I had already begun moving away from traditional graphic design projects. I began studying graphic design in 1997, receiving my BFA in 2002. In 2004, I began working at Linotype, as a marketer (and want-to-be typeface designer), thrusting me into a separate, but related industry. Am I even a graphic designer anymore? This is probably a topic best left for a separate article. However, I think the question explains why I hadn’t felt the urge to do more than flip through pages of How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul in bookstores. I read the cover, and said, “this book was not for me.” I shouldn’t have judged the book by its cover.

Things about the book that I do not like

At times, Shaughnessy’s text feels very UK-specific, or even London-specific. Several times during my reading of the book, I asked myself whether the advice would be as applicable elsewhere. How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul seems as if it would also be of much help to designers working in New York, but what about advice seekers living in smaller US towns and cities, or in continental Europe, or even farther afield … such as in the Arab Gulf states, or India? Perhaps my concerns are too inflated, as the first edition of How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul was translated into seven languages. Clearly, there are other publishers and readers who have found the book’s content relevant.

Some of the Shaughnessy’s recollections fall into the “I’ve been a successful designer for decades, and I also ran a large studio for many years, so here is what I did in a specific situation some time ago” category. On the other hand, Shaughnessy couches many of these decisions, especially those where he came to a conclusion that went against his better judgement, or even against the advice he is writing to others via this book.

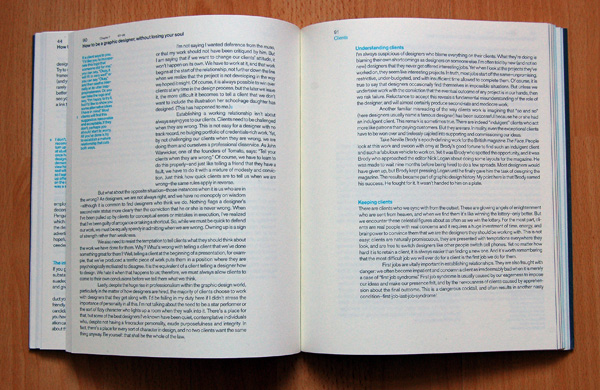

There could be more advice about how to get clients, and where a designer finds them. Chapter 7 of the book is entitled “Clients,” but is just nine pages long. Although, as I mentioned above, most of this book’s chapters are brief; there are three others that are also nine-pages in length.

Finally, there is not much definition of what a graphic designer’s “soul” is, or how one might loose it, at least not in the same manner as Milton Glaser writes in his article, the Road to Hell.

The design of this book as an object

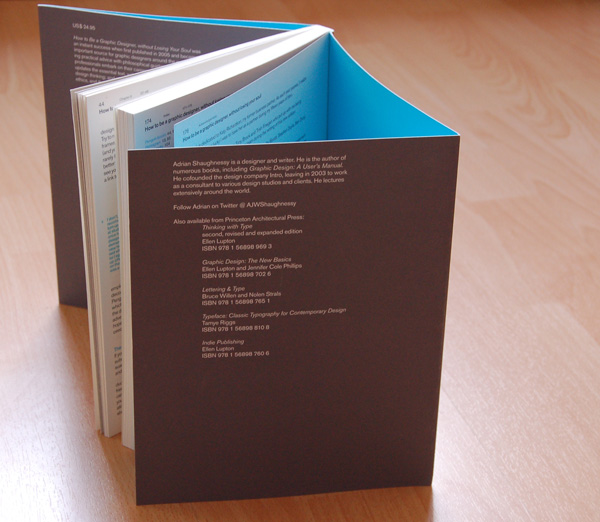

How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul measures 23cm tall by 19cm wide by 1.5cm deep, when closed. The book is a paperback, with long cover flaps.

This excellent design decision is offset by a poor binding of the cover to the book block (too much glue, I think), and I am not sure that the best cover stock was selected—I don’t like to see creases or breaks in my book after just the first reading.

All of my cover concerns are made up for after touching the book’s block itself. The uncoated pages are a delight in the hand. The paper is a heavier stock, and is slightly off-white. Text is printed in two colors: gray for text, and blue for subheads and side notes. There are a lot of side notes, and the way that these integrate with the main text is interesting; they cause the page’s grid to change, diving a dynamism to the book as a whole.

The typeface selection could be improved, should a third edition be printed. The face used is Akzidenz-Grotesk, which seems to have been selected because it is a popular, dogmatic typeface for graphic designers in the know, rather than for any inherent legibility. The capital letters are slightly too dark, and slightly too close to the lowercase letters that follow them in a word. Within the present page layout, a study serif of slab serif typeface would make an equally striking effect, and would be of more benefit to the reader.

Conclusions

I recommend How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul; in fact, I wish that the book had been recommended to me years ago. It is a pity that I never read it before. Moreover, I recommend this second edition, as it includes more chapters, and its advice has been updated in light of the 2008 global economic crisis.[2] This book could be a helpful gift to older design students, and to young professionals. For $24.95, one can hardly go wrong. This book is worth the risk and small investment.

The book’s details

How to be a graphic designer without losing your soul. Second edition.

By Adrian Shaughnessy

Princeton Architectural Press (2010)

ISBN: 978-1-56898-983-9

19cm wide by 23cm tall

176 pages. Paperback with flaps

$24.95 at papress.com or amazon.com

Footnotes

- A friend of mine calls this phenomenon “Bonn Republic thinking,” referring to the mentality of Wirtschaftswunder-era West Germany.

- In his introduction to the new edition, Shaughnessy also mentions that the book has been updated to reflect the changes in social connectivity since 2004, although I do not recall any specific recounts of social networking strategies being discussed.